Expectations from the higher judiciary are so low in Jharkhand that even when a mind-blowing building of the new Jharkhand High Court is set to open in Ranchi on May 24, 2023, it has raised eyebrows of many common citizens questioning whether honourable judges deserve it.

Serving as a temple of the judiciary, this building’s marvellous design was obviously influenced by its function. The building conjures images of modernity and luxury complete with a series of rings. A truly eye-opening building that’s both unique and inspiring.And built at a high cost of over Rs 600 crore.

In terms of 90 acres of land area covering this new high court building, it is larger than any of the high courts of India and even the Supreme Court (22 acres).

The building has 500 CCTV cameras, In all 1,200 advocates will sit in two halls with separate 540 chambers and the advocate general building separately.

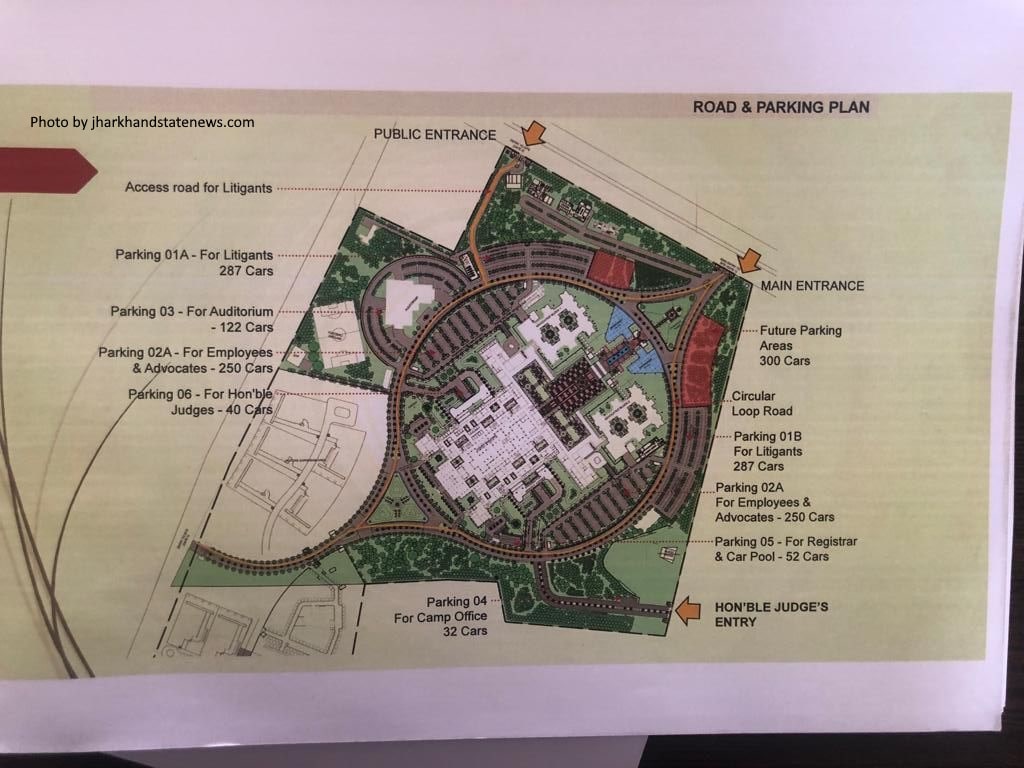

It has a library built in 30,000 square feet along with parking arrangements for 2,000 vehicles and is centrally air-conditioned with 25 grand air-conditioned courtrooms for hearing cases.

The library has more than five lakh legal books in which judges and other judicial officers can sit and study.

Three blocks have been made in the high court building on about 68 acres. The judicial block has two floors. Of these, a total of 13 courts, including the chief justice’s court have been constructed on the first floor, while 12 courts have been built on the second floor.

There is a separate chamber for typists. Apart from this, barracks have also been constructed for 70 policemen.

The advocate general’s office has been created separately. There will be a chamber of the advocate general, four additional advocates general and a chamber for 95 government advocates.

Apart from this, a conference hall has also been made with seating arrangements for 30 people. The total construction area of the new high court building is around 68 acres, with parking, a courtroom, an advocate hall, a registry building and other arrangements.

A total of 4,436 saplings, many of life-size height, each costing thousands of rupees have been planted to keep the campus green. A post office, dispensary, railway booking counter and a crèche have also been constructed in the complex.

The campus will be lit by solar energy. About 60 per cent of the power supply in the entire region will be from solar energy only. For this, a 2,000 KVA solar power plant has been set up in the parking area.

Apart from this, 2,000 KV generators have also been installed to provide power backup, in which there is one 1,500 KV and two generators of 500-500 KV capacity.

Do honourable judges deserve all these? Some advocates say they deserve much more than what they get.

But the answer may be “no” as well, not because judges are inept morally, but because the institutional setting in which they act and the role that they adopt both require them to address questions about rights in a particular legalistic way—indeed, in a way that, sometimes, makes it harder rather than easier for essential moral questions to be identified and addressed in this country and state where a vast majority of tribals live below the poverty line.

Of course, what this land of tribals needs is for moral and legal issues to be addressed quickly and smartly, not as one would make a personal moral decision, but in the name of the whole society.

Perhaps the judicial mode of addressing them satisfies that description, but there are other ways of satisfying it too—including pro-poor judicial approaches, a phenomenon missing in the current mode of judicial function.

Which is why the question proceeds by identifying all the issues and all the opinions that might be relevant to a decision, rather than artificially limiting them in the way that higher court act towards the legal rights of poor and common citizens of the country.