Representational Picture

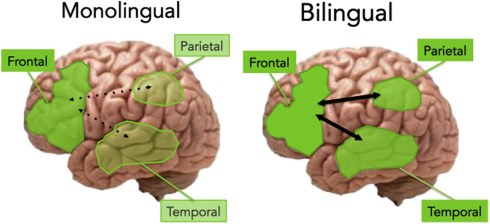

People who speak two languages have more grey matter in the executive control region of the brain, a new study has found.

Earlier, bilingualism was thought to be a disadvantage because the presence of two vocabularies would lead to delayed language development in children.

However, it has since been demonstrated that bilingual individuals perform better, compared with monolinguals, on tasks that require attention, inhibition and short-term memory, collectively termed “executive control”.

“Inconsistencies in the reports about the bilingual advantage stem primarily from the variety of tasks that are used in attempts to elicit the advantage,” said senior author Guinevere Eden, director for the Centre for the Study of Learning at Georgetown University Medical Centre (GUMC).

“Given this concern, we took a different approach and instead compared grey matter volume between adult bilinguals and monolinguals,” Eden said.

“We reasoned that the experience with two languages and the increased need for cognitive control to use them appropriately would result in brain changes in Spanish-English bilinguals when compared with English-speaking monolinguals,” he added.

“And in fact greater grey matter for bilinguals was observed in frontal and parietal brain regions that are involved in executive control,” Eden said.

Grey matter of the brain has been shown to differ in volume as a function of people’s experiences.

“Our aim was to address whether the constant management of two spoken languages leads to cognitive advantages and the larger grey matter we observed in Spanish-English bilinguals, or whether other aspects of being bilingual, such as the large vocabulary associated with having two languages, could account for this,” said lead author Olumide Olulade, post-doctoral fellow at GUMC.

The researchers compared grey matter in bilinguals of American Sign Language (ASL) and spoken English with monolingual users of English.

Both ASL-English and Spanish-English bilinguals share qualities associated with bilingualism, such as vocabulary size. However, unlike bilinguals of two spoken languages, ASL-English bilinguals can sign and speak simultaneously, allowing the researchers to test whether the need to inhibit the other language might explain the bilingual advantage.

“Unlike the findings for the Spanish-English bilinguals, we found no evidence for greater grey matter in the ASL-English bilinguals,” Olulade said.

“Thus we conclude that the management of two spoken languages in the same modality, rather than simply a larger vocabulary, leads to the differences we observed in the Spanish-English bilinguals,” he added.

The study was published in the journal Cerebral Cortex.